In my experience so far as a School Psychologist, one of the recurring themes has been the nature of assessment. Few issues have garnered as much reflection in the literature, or have been so important in defining the role of the SP. Since the ‘reconstruction’ movement launched itself in the 1970s, the School Psychology profession has been caught in a seemingly never-ending debate on the pros and cons of psychometric assessment. Occasionally, some poor soul will ask an innocent question about scoring or reporting on an SP email chain, only to find they have unwittingly re-ignited the always simmering civil war within the profession, in regards the use of psychometric assessment.

As far as I am concerned, this division exists in the profession, in my School Psychology Service, and even within myself. I have yet to reach a conclusion as to exactly where I stand on this issue, and have reflected on this in past portfolios. Given that this year I have purposefully engaged in psychometric assessments, in order to further develop and understand my own stance, I feel it is an appropriate topic for my final extended piece. I have chosen to explore psychometric assessment as it sits alongside inclusion, another issue in which there are mixed understandings and opinions, and one no less relevant to an SP.

In this extended piece, I aim to draw together my experiences, my new learning, the wider literature and my local authority context to reconstruct a relevant, sense-making, useful understanding of psychometric assessment and inclusion. Rather than define inclusion from the offset, I will begin by exploring how it is constructed and defined in practice and how SPs should respond to these constructions. Following this I will look at psychometric assessment from different perspectives, and conclude by discussing whether it can co-exist peacefully with inclusive practice, however we choose to define it.

Inclusion in Context

The work of an SP, at least from my perspective from September, takes place within the context of a local authority School Psychology Service, itself subject to legislation from the government. This context could be seen as guiding our role, defining our role, or perhaps constraining our role. The SEND Code of Practice states ‘the UK Government is committed to inclusive education of disabled children and young people and the progressive removal of barriers to learning and participation in mainstream education’ (Department for Education, 2015, p. 25). Beyond this statement, there is no further definition of inclusion or inclusive education, although there is reference to presumption of mainstream education secured in the Children and Families Act 2014. Inclusion appears to relate to integration, pupil achievement, and access to the National Curriculum. There is an understanding of ‘disabled children and young people’ as a discrete group. In turn, my School Psychology service literature discuss ‘inclusive’ schools being at the heart of their aspirations. Again, this is not explicitly defined, but there is reference made to wellbeing, participation and achievement of children and young people in educational contexts, as well as gathering information on their strengths, needs and aspirations.

In reality, these inclusive aspirations are taking place within a national context of an increasingly neoliberal education system. The tension between these two models is apparent, as inclusive education ‘emphasises belonging, acceptance, community support and interdependence. [Neoliberalism] promotes individual achievement, academic excellence and aggressive independence’ (Goodley & Billington, 2017, p. 69). ‘This liminal space feels like having to take sides and challenges the supposedly neutral space inhabited by SPs’ (Devlin, 2017, p. 91). The SP work is defined within this context of contradiction, and it is clear why so many authors have returned to the question of what our role is, or should be. To resolve this cognitive dissonance, it feels like I must either bite the hand that feeds me, or I must retire to a smaller notion of inclusion.

‘Are we talking about where children are placed and with what level of resource provision? Or, are we talking about the politics of value, about the purpose and content of curriculum, and about the range and conduct of pedagogy?’ (Slee, 1997, p. 412)

Often within the context of writing statutory advice, I must admit that I have more experience with the former than the latter. It is with this knowledge that my own practice is not what I would hope it to be, that I wish to look at the role of the SP with regards inclusion, with reference to my own experiences, and with reference to my own limitations.

Individual Child Assessment

The role of the SP has been often been defined in terms of its functions, perhaps the most cited example being the Currie Matrix (Scottish Executive, 2002), defining the core functions as assessment, consultation, intervention, research and training. SP work is seen as occurring at three different levels: the child and family level, the school level, and the local authority level (Scottish Executive, 2002). I will discuss the SP role within the child and family level, as it relates to individual assessment.

The Currie Report, mentioned above, was conducted within a context of SP’s promoting inclusion, and it noted that SPs have moved away from a medical model towards working ‘with and through others in a consultative, facilitative capacity’ (Scottish Executive, 2002, p. 20), with a focus on adjusting environmental and teaching variables. However, it also noted that 39% of SPs consulted felt that they still did too much assessment. There was little information given as to what assessment might consist of. Passenger (2013, p. 22) suggests that within modern School Psychology, SPs ‘no longer arrived at school carrying a ‘black bag’ with a standardized intelligence test’ (a direct contradiction of what I have observed in practice, although only by some SPs). However, she goes on to note that intelligence testing remains the most popular type of assessment worldwide. Ashton and Roberts (2006) suggest that individual and statutory assessment remain the most sought after input for an SP. SPs are, of course, obliged to assess and write statutory psychological advice for individual children, couched in terms of identifying needs, outcomes and provision, based on an understanding that ‘Children and young people with SEN have different needs…’ (Department for Education, 2015, p. 28).

Since the publication of the Warnock Report in 1978, there was an emphasis on moving away from use of assessment to diagnose and classify, towards use of individualised descriptions of the needs of children. ‘Eschewing a medical model of diagnosis, the focus was fundamentally educational and problem based’ explain Tymms and Elliott (2006, p. 25), warning that the intended results may not have been produced, and there has been a swing back towards cognitive assessments to diagnose and label special educational needs. It is worth considering the context in which such tests first bloomed in popularity. As national education systems expanded to include a much higher population of children and young people, ‘teachers found themselves confronted by significant numbers of children who appeared incapable of coping with the academic demands’ (J. Elliott, 2003, p. 15). In this context, difficulties were reframed into ‘two interrelated problems – inefficient organisations and defective students’ (Skrtic, 1991, p. 152). This sounds similar to many classrooms today, especially as academic standards continue to be driven up, and many schools are struggling with resources due to ongoing austerity measures, whilst hoping to avoid negative inspection results from Ofsted. Although there are conversations to be had about the systems in place around the child, in my experience school staff are much more comfortable focusing on the child’s deficits. At worst, schools will protest that they are not the appropriate provision for this child, with their difficulties. There can be real pressures to conduct psychometric tests, either to access resources, or to justify slow progress of learning. How should SPs engage with this? The approach used by many practicing SPs, in my experience, is that there is a place for cognitive, norm-reference tests, to shine a light on strengths and weaknesses, but this information must be interpreted within the context of the child’s surrounding environment. Is this a valid approach, or are norm-referenced assessments entirely incompatible with inclusion? I will begin my exploration of psychometric assessments by looking at the assumptions of validity for their use.

Psychometrics and Validity

Standardised intelligence tests have received their fair share of criticism since the 1970s, with commentators noting that they are biased toward minority groups and children who may have a label of special educational needs (SEN), as well as those who may have not been exposed to adequate learning opportunities: ‘Their failure does not reflect lack of intellectual ability but rather lack of learning strategies, learning habits, and motivation to master cognitive tasks’ (Tzuriel, 2012, p. 1). Haywood and Lidz (2006) note that such tests often measure past learning. Whilst this can be predictive of future learning, they warn that it is not a perfect correlation and such thinking runs the risk of becoming a self-fulfilling prophecy. When children have not been exposed to the same learning opportunities as their peers, it is apparent how viewing the child within the context of norm-referenced scores could prove very limiting. Focusing on within-child variables has also been seen as shifting focus from other variable which may be more amenable to change, such as ‘quality of teaching or parenting, classroom organisation, the selection of appropriate learning and developmental objectives, the consideration of effective methods of teaching…’(Cameron & Hardy, 2013, p. 81). As proponents of Dynamic Assessment would argue, static testing excludes non-intellective variables that are integral to success in school and in life.

There have also been concerns over the years that intelligence testing lacks a coherent theory upon which it is based. In recent years, intelligence theorists have moved to right this wrong, leading to the generation of ‘second generation’ ability tests, that have a footing in theory (Naglieri, 2015). These tests were designed such that they measured academic achievement as different from ability, in order to put more emphasis on cognitive activities rather than acquired knowledge, in order to measure ability. Naglieri (2015) notes that traditional test batteries use similar verbal and arithmetic measures in both the achievement and ability subtests, which is problematic as the correlation between IQ and achievement scores has traditionally been considered evidence for the validity of the IQ measure. He makes reference to WISCs and WIATs in this criticism. In second generation tests, without the verbal and arithmetic ‘achievement’ type questions in the ability subtests, Naglieri (2015, p. 300) finds that correlation between achievement and ability scales were as high or higher than in the traditional tests, and concludes that this predictive validity shows that cognitive approaches to intelligence ‘provides an advantage for understanding achievement strengths and weaknesses for children who come from disadvantaged environments as well as those who have a history of academic failure’. In my practice, I have witnessed SP using cognitive tests to look at specific subscales, or to engage with profile analysis to suggest strengths and weaknesses without reducing the child to a single, and powerful number such as an IQ score. I have engaged with this myself. However, this is seen as problematic due to ‘limitations in subtest reliability and validity’ (Naglieri, 2015, p. 300).

A recurring criticism of using standardised tests is that they do not provide information or strategies to help practitioners plan interventions (Gillham, 1978; Lauchlan, 2001). This point is also refuted by Naglieri (2015, p. 304), who notes that ‘the relationships between cognitive abilities as measured by the CAS [Cognitive Assessment System] and academic instruction have been reported in a series of research papers’. It should be noted that Naglieri is the one of the authors of the CAS, and is certainly not an independent observer. What is most concerning about this discussion of second wave intelligence tests is that the Wechsler products appear to be part of the first wave traditional approaches that are being criticised. These are the products I have seen used most often within SP practice, as is noted in the literature (Kaufman, 2000). Indeed, most of the criticisms that SP literature have about these tests are the same criticisms that those within cognitive psychology have, and yet their response has been to reform. Do these second generation test resolve the issues and concerns that many have about psychometric approaches, or are there larger, epistemological concerns associated with such use of essentialist approaches? I will explore this question by looking at the assumptions and the implications that come with individual ability testing.

Psychometrics and Ontology

According to Hood (2013), it is often assumed that use of psychometrics implies a commitment to realism, in that there is a belief that you are measuring something that exists. However, he suggests that a realist commitment to latent ability traits is only necessary when attempting to measure ability. In contrast, if the attribute being measured is considered a hypothesis, and it is being used for predicting performance, there need not be a commitment to ontological realism. From this perspective, a defence could be mounted that use of psychometrics can be based on theory, where the attribute being measured is ‘a mere placeholder for confounding causal factors yet to be distangled’ (Hood, 2013, p. 753), and isn’t necessarily based on an uncritical realist assumption of cognitive structures of intelligence. ‘One might even argue that is just good science to withhold ontological commitments until sufficient evidence has accumulated that would warrant beliefs in latent traits’ (Hood, 2013, p. 750). Such a view might be seen as coherent with contemporary SP views on assessment: ‘The key characteristic of psychological assessment is that they hypotheses which drive practitioner’s thinking and problem solving are drawn from psychological theory and research’ (Cameron & Hardy, 2013, p. 89). Could psychometric scores as ‘predictors’ of performance be useful to SP, without the commitment to underlying factors? For example, a measure of working memory providing predictive information on what a child might find difficult in a classroom context. This might avoid ontological confusion, but in practice the difficulties have usually already been observed, and it is the cause of the difficulties that teachers are interested in. Indeed, such use of tests has been criticised as being unhelpful to teachers.

Robinson (2014) proposes that the use of psychometric tests is, in practice, more interpretative than one would suppose, which calls into question the test validity of such approaches. He notes that there is a level of interpretation involved in how participants perceive and respond to texts or questions, which can be ambiguous. Robinson also notes the interpretative role on those administering the test, particularly when questions require open-ended spoken responses from the participant. ‘While not all psychologists who employ these methods fully own up to the deeply interpretative nature of their methods, it is a fact that is being increasingly recognised in the literature’ (Robinson, 2014, p. 7). A number of researchers have questioned the validity of such approaches to measure anything at all, suggesting ability tests can only rank information: ‘This ranking does not in any way permit the claim that “cognitive ability” is therefore being measured because ranking itself is not measurement’ (Garrison, 2007, p. 818). Thomas and Loxley (2007) continue this criticism, suggesting that the theorised cognitive structures of the mind are nothing more than metaphor, and categories of mind are just faculties, that do not provide any explanation.

The methodologies on which ability tests are often based, such as hypothetico-deductivism, have also received criticism from of being elitist, inconsistent and full of anomalies (Willig, 2013). ‘One devastating consequence of this approach was the utter dismissal and denigration of human emotion, physical sensation, intuition, and spontaneous improvisation, without which it is nearly impossible to imagine being able to “think” or lead a healthy, interesting, and successful life’ (Brownstein, 2007, p. 515). I will continue this line of thought in the following sections, exploring how the philosophy of psychometric assessments can impact on our political world.

Psychometrics and Politics

As discussed above, arguments can, and are, being made for the usefulness of intelligence testing. Within cognitive psychology, there is a paradigm in which such tests are useful, and such understanding of children is beneficial, however, as I have discussed there are many who would question the paradigm. Regardless of SP intent, it is still apparent that ‘Traditional tests tend to produce clear-cut results that are used to evaluate, identify and classify children’ (Caffrey, Fuchs, & Fuchs, 2008, p. 254). For Szulevicz and Tanggaard (2016, p. 37), this view is problematic when considering inclusion: ‘The inclusion concept is instead based on a relational approach, whereby special needs are not considered to be a characteristic of the individual child’. A critical look at the SEND Code of Practice might allow one to consider SEN not as a characteristic of the child or young person, but rather to take the approach that, ‘special needs must be understood in relation to the way that our education system functions’ (Szulevicz & Tanggaard, 2016, p. 37). Kaufman (2000, p. 13), himself vocal on the positive utility of intelligence testing concludes that it is not the scores themselves, but rather how they are used and understood, where the problem lies:

‘It is this basic conflict between the intelligent use of IQ tests, which fosters understanding a person’s strengths and weaknesses and using the results of the evaluation to help children, and how educational decisions are made, that has led to many of the controversies over the years’.

He places the problem at the feet of government agencies ‘forcing’ psychologists to use the scores to make placement and diagnostic decisions. Boyle (2014) further discusses how the work of SPs is guided by politicians and policies, as well as an historical understanding of the work of SPs largely consisting of testing individual pupils to find and quantify weaknesses. ‘This forms the basis of a model of deficit, which is not absolutely helpful in considering a balanced approach to support in schools or in the community’ (Boyle, 2014, p. 86). He does not reject cognitive testing entirely, but suggests that on its own, it is a poor demonstration of psychological approaches and knowledge. In my experience, having a number of schools who have purchased very small amounts of SP time, there is often a demand for ‘scores’ and little time to explore alternative options. This is in a context where private psychologists practice and offer isolated cognitive assessments for schools to purchase at competitive prices.

To bring things back to inclusion, is it sensible to engage with standardised approaches that systems may use to define and exclude children, based on an individualistic understanding of intelligence? It has been observed that minorities are overrepresented within special education (Skiba et al., 2008; Slee, 1997), a fact which has troubling implications if we see the processes of labelling and categorising as objective, and if we see intelligence as innate and measureable. Can we rightly carry on, without accepting responsibility for how scores are understood and used? In rejecting standardised approaches wholeheartedly, or holding steadfastly to out of date materials, is there a danger of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, particularly if such approaches can be useful in planning interventions and understanding strengths and difficulties of children and young people? Below, I widen the lens to look at impact of positivist understandings of individuals on larger societal understandings and structures.

Positivism in Context

Brownstein (2007, p. 515) uses the approach of critical epistemology to problematize positivist approaches in education, suggesting that tests used to quantify human learning ‘reveal more about the values and cultural assumptions of those who construct the tests and the students familiarity with cultural norms…of the dominant class than they do about the critical and creative qualities of how students process and apply what they know’. Writing from a US perspective, she suggests the purpose of education is thus to reinforce class structures to protect the dominant classes. This line of thinking is what Thomas and Loxley (2007) might label as a strong version of critical theory, with assumptions of intent. They suggest that even without assumption of intent to reinforce class structures, if the people who run our education systems believe social reality is objective and rational, it leads to the same outcomes, as education problems are seen as pathological, located in individual pupils, and individual schools. As Prilleltensky and Fox (1997, p. 12) warn ‘A philosophy of individualism, explaining problems as purely individual, leads to a search for purely individual solutions’. In this way, critique of larger, societal issues and inequalities is avoided. As mentioned above, UK education is becoming increasingly neoliberal. ‘For neoliberals, those who do not succeed are held to have made bad choices. Personal responsibility means nothing is society’s fault. People have only themselves to blame,’ note Hursh and Martina (2003, p. 497). In short, it is an understanding of society as a meritocracy, where those at the top are virtuous and deserve to be in the ruling class, and those at the bottom are not there by chance. Garrison (2007, p. 820) goes so far as to suggest that the role of standardized assessments of IQ or ability are, in truth, an assessment of social value, ‘a conjecture that is supported by the relatively strong correlation of test scores with socio-economic status…compared to the relatively weak correlation of ability and achievement tests with performance outside academe’.

Within the performative context of neoliberal education systems, curricular goals are framed in terms of individual pupils having marketable abilities to compete and contribute to the nation’s economy within a system of global competition (Patrick, 2013). Schools are held under increased scrutiny to increase standards (in terms of intellectual capacities of individuals) and ‘those learners with learning difficulties become problematic for schools […] likely to have a detrimental impact on school performance data (Glazzard, 2011, p. 59). Schools which perform well in league tables are not often the same schools that show success in catering for pupils with special educational needs (SEN) labels (Lunt & Norwich, 2008), and schools and teachers are aware of this (Hick, Kershner, & Farrell, 2009). They are left with the choice of locating the problem within the individually failing school, or within the individually failing child, as noted above. In this context, can SPs be sure that conducting psychometric tests in order to gather strengths and weaknesses won’t be used to categorize and label in ways that do not serve to support the child, but rather to protect the school, and the wider system in play. Is this inclusive practice? ‘The idea of categorisation and thus labelling is anathema to what school psychologists should be attempting to do in invoking natural justice for clients…’ (Boyle, 2014, p. 91). As the role of the SP has often been characterised in terms of assessment of pupil needs, strengths and weaknesses, how can we perform this task in a way that sidesteps use of psychometric testing and avoids risk of contributing to exclusionary forces?

Working in an Inclusive Way

This may be a good moment to suggest exactly what we are talking about when we talk about inclusion. I have up to now looked at the ideas of psychometric assessment, and how they sit alongside the potential exclusion and differentiating of children and young people. Within a neoliberal education system, how we conceptualise the needs of young people may be thought of as individuals ‘having to adjust to the requirements of the school, its norms and values’ (Szulevicz & Tanggaard, 2016, p. 36). This is the definition of integration. Assessing children within this context allies itself within a deficit approach, in which the aim of education is to promote child development ‘by moving the child in tiny steps towards an approximate norm’ (Rees, 2017, p. 33). Inclusion, however, may be seen as something radically different, a move from:

‘…a one-dimensional landscape – primarily about disability and difficulty – to a three-dimensional terrain that now incorporates a more extensive spectrum of concerns and discourses about the benefits that come from valuing diversity.’ (Thomas, 2013, p. 474)

This move away from a simplistic view of integrating those with disabilities is understood in contemporary views of inclusion. One oft-cited definition of inclusion comes from Farrell (2004), who suggests that for a school to be inclusive, alongside pupils being present, they also:

‘…need to be accepted by their peers and by staff, they need to participate in all the school’s activities and they need to attain good levels of achievement in their work and behaviour’ (Farrell, 2004, pp. 8-9).

Looking at inclusion in this way can prompt schools to examine current systems, policies and ethos of their school (Farrell, 2004). This implies that an inclusive approach should concern itself with seeking change in schools, and communities, rather than just within individual pupils (Szulevicz & Tanggaard, 2016). In Slee’s (1997) problematisation of essentialist special education theory, he proposes that we must begin by acknowledging ‘the diversity of identities which have hitherto been collapsed into special education categories’ and build cultures around them. This is no less than a restructuring of much of our education and schooling systems, which is undoubtedly a tall order. Where does one begin?

Prilleltensky (2014) provides a possible starting point, by analysing educational, social and health interventions according to four dimensions: competency, time, engagement, and focus (see Table 1).

| Deficit-oriented | Competency | Strength-based |

| Reactive | Time | Preventive |

| Alienating | Engagement | Empowering |

| INdividualistic | Focus | Community-based |

Table 1 – Dimensions of Intervention (adapted from Prilleltensky, 2014)

Prilleltensky (2014) proposes that traditional individualistic approaches have created what he terms a DRAIN approach in psychology. This is an acronym of Deficit-oriented, Reactive, Alienating, and Individualistic, an approach he suggests ‘represents the interests of government and power elites (Prilleltensky, 2014, p. 18). His suggested alternative approach is a SPEC approach, which is Strengths-based, Preventive, Empowering and Community-based.

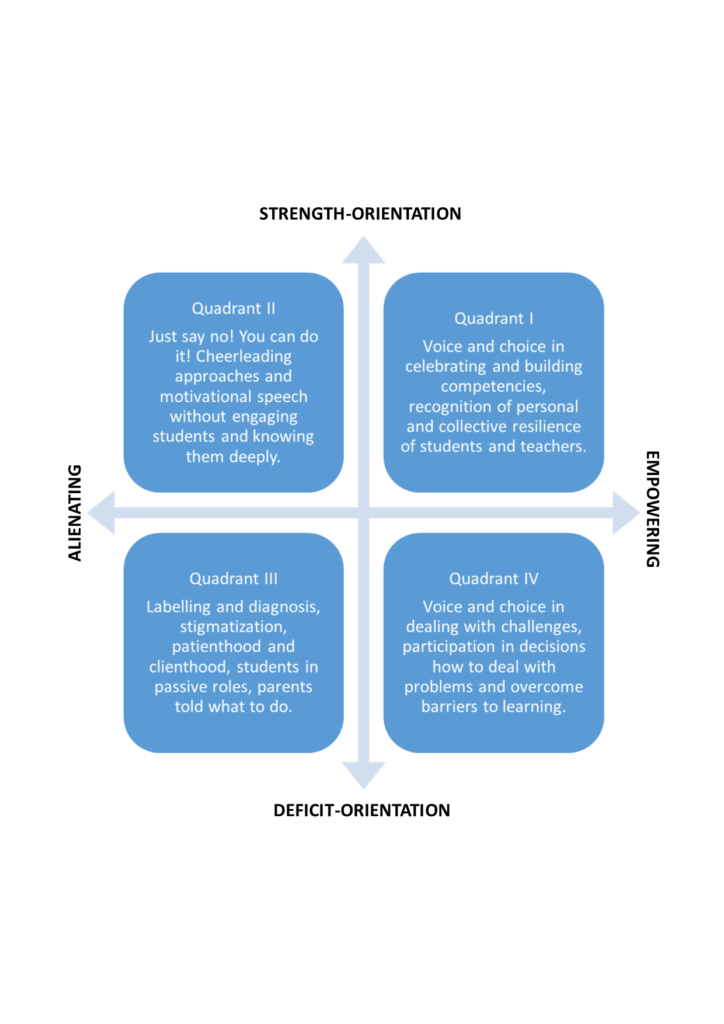

These two approaches can be compared and contrasted in two different fields. The first is the Affirmation field (see Figure 1), consisting of the competency and engagement dimensions. Prilleltensky (2014) proposes that a strength-based, empowering approach can be an alternative to labelling, stigmatizing approaches, and can be used to celebrate pupils’ abilities to cope and thrive. Alongside this, there should be an emphasis on voice and choice to engage pupils (as well as their families and teachers). ‘…we know that alienating practices fail to achieve desired results because people are psychologically disengaged’ (Prilleltensky, 2014, p. 27). This could involve the use of approaches such as Video Interaction Guidance, which is a positive intervention based on beliefs of respect and empowerment (Kennedy, 2011), or Narrative Therapy, which avoids essentialist and deficit-based assumptions (Payne, 2006). Referring back to Farrell’s (2004) principles of inclusion, these approaches could be seen a supporting acceptance of pupils, by avoiding a focus that could stigmatize. They might also be seen as promoting participation of pupils, with the emphasis on voice and choice.

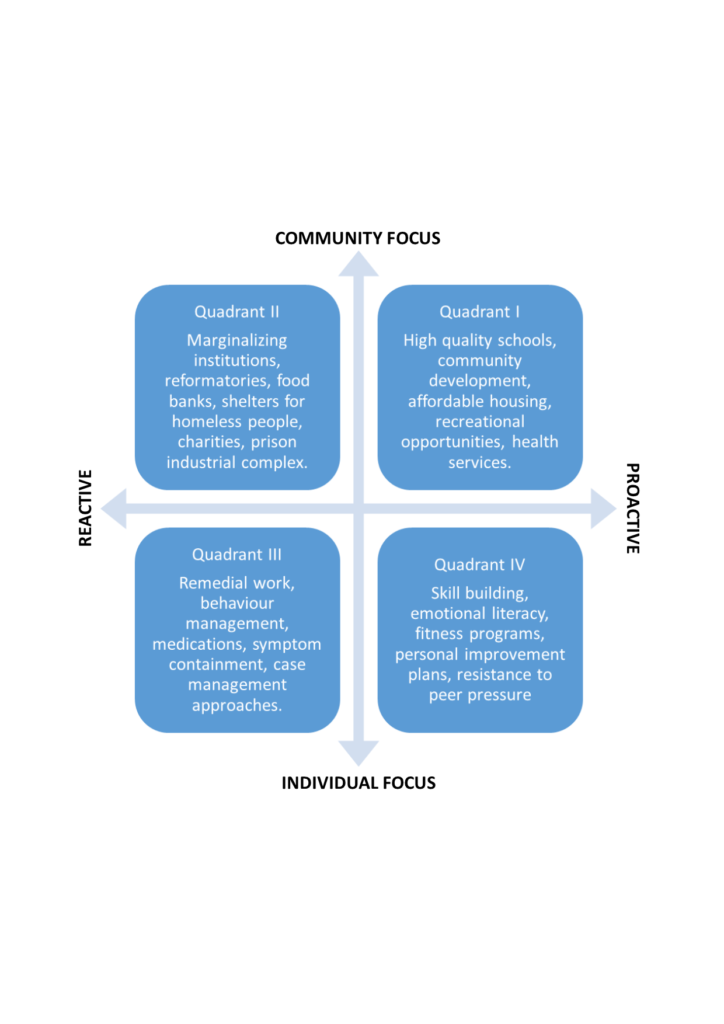

The second field in which we can compare these approaches is the Contextual Field (see Figure 2), which looks at the timing and focus of the interventions. In this field, the SPEC approach emphasises proactive, community-based interventions. In this context of School Psychology, this could involve promoting staff training opportunities as a use of SP time, rather than assessment work. It could also include promotion and facilitating of proactive, group approaches in the classroom, such as Philosophy for Children (Trickey & Topping, 2004). Here we can see the emphasis on community rather than individual approaches could support Farrell’s (2004) inclusive principle of pupils being present, as there is no drive to remove or exclude individuals. This approach can also be seen to support pupil achievement, with a proactive emphasis on skill building, for example.

Conclusion

In this extended piece, I have explored the place of psychometric testing within School Psychology, and within education in general. As can be seen in the discussion above, it is very possible for SPs to work in ways that promote inclusion, whilst addressing the needs and promoting strengths of the whole school community, in a way that does not necessitate the use of psychometric tests. Is there therefore no place in SP practice for the use of psychometric tests?

I don’t believe I can, or should, conclude with a hard yes or no, as to whether there is any sort of place in contemporary School Psychology for psychometric tests. Rather, I would suggest a number of considerations would need to be taken into account, for example:

- Are the tests being used to find deficits, or unmet needs?

- How are the scores likely to be used, once out of the SP’s control?

- Are they part of a larger contextual assessment, in which the child is actively participating?

- Will use of test be likely to contribute to stigmatization or exclusion of pupil?

- Is it likely to be an empowering or alienating experience for the pupil?

- Is there an alternative approach for this situation?

It is the last question which might constrain a school, and the role of the SP may be to illuminate and explore alternative approaches. As Boyle (2014, p. 92) says, ‘…there are so many robust psychological interventions that could be enhancing the profession but it is a pity that so many choose psychometrics over innovation’. My experience on placement in an School Psychology Service, working within a number of different schools and staff, suggests that traditional forms of SP work are cohabiting alongside more progressive forms of SP work. The degree to which School Psychology as a profession is changing or progressing is a matter of how much each individual SP is changing and progressing, as well as how much new recruits differ in their practice from those who are retiring. In turn, schools have differing expectations from their SPs, and hold wide-ranging views on the usefulness of psychometric testing. I believe I have demonstrated that it is possible to practice without the use of psychometric testing, and this may be more conducive to inclusive practice.